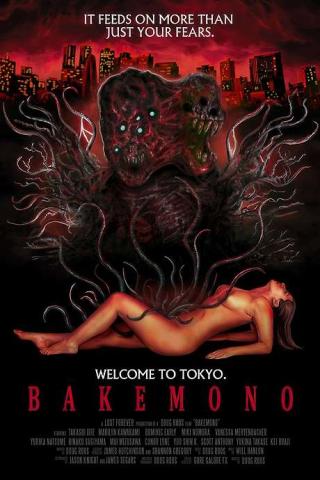

A multitude of guests visit the same cheap Tokyo airbnb at different times, unaware of the gruesome creature waiting for them.

Late at night in the backstreets of Tokyo, a woman (Hanaka Mizuki) arrives with a wheeled suitcase at a dingy, ‘creepy’ rental apartment, where, terrified, she is attacked in the dark by a fleshy, half-glimpsed creature. This is the bakemono, or ‘monster’, of the film’s title, explained in text as a composite of bake, ‘changing’ or ‘transforming’, and mono, ‘thing’ or ‘creature’ – although far from being a shapeshifting yokai of Japanese mythology, this is rather a demon raised via instructions in by Crowleyan magick from a copy of The Lesser Key of Solomon, left in a drawer where one might more normally find a Gideons Bible.

This assault on the woman may be only the opening scene in Bakemono, but in essence it is every scene from a film which comprises sequences set in and around the haunted apartment, with its cement-rendered walls and bad odours, its lights that fail and its front door that will not open. These scenes are intercut in such a way as to present a very peculiar chronotope: for while space here is mostly fixed and confined to the environs of the Airbnb, time proves far more fluid, as different scenarios overlap and echo each other, with only the personnel and their internal dynamics varying, so that the impression quickly establishes itself of a serial yet parallel fate whose bludgeoning iterations seem to allow for no escape. The set-up is not unlike that of Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) and its many related films, whose constituent episodes, though reshuffled out of chronological order, always lead to the same ineluctable doom. In Bakemono too, history keeps repeating, as a nation’s lived-in manners and mores engender horror upon horror.

“This city gets to you after a while… It chews you up. Pits you against each other. Isolates. Buries you under stress… If you’re depressed, it’ll crush you on the train tracks and make your family pay for it. Overwork. Gender rôles. The hierarchy. … It makes everything worse. Changes you.” The speaker is Anna (Marilyn Kawakami), who has come to the apartment with her friend Risa (Miki Nomura) – and although she does not know it, Anna’s words apply equally to the creature within, which sets friends, family and lovers against one another, such that, amid all the violent fighting and feuding, its own tentacular assaults seem a mere mirror. Anna is expressly laying out the realities that underlie this film’s fictions: a kind of horror that is more urban than supernatural, showing the darker side of life in Tokyo, with sexual inequality, the objectification of women and rape itself emerging time and again from the shadows.

Even within the film, the irrational is always playing tag team with the rational. For as Anna chats with Risa, her every word is being monitored via a spycam by Mitsuo (Takashi Irie), the married, middle-aged owner of the apartment who secretly moonlights as a serial rapist, killer and satanist. We remain unsure whether the monster that Mitsuo has ritually conjured is real, or a mere manifestation of Mitsuo’s own perverse drives and negative emotions, exposed from the inside out.

Mitsuo himself, for all his repellent misogyny and abominable acts, seems real enough, especially in his use of picnic coolers filled with cat litter for disposing of his victims’ body parts, which recalls the modus operandi of real-life serial killer Takahiro Shiraishi. There may be a resident evil here which comes out at midnight to prey on people’s psychological weakness and to compete with Mitsuo in murder, but it also serves as an expression of Mitsuo’s double-life as family man and murderous monster. The greatest challenge to the creature’s onslaught is Chris (Dominic Early), an African-American outsider in Tokyo for work, who like Mitsuo has a wife and child at home, but unlike Mitsuo is kind, caring and ‘nice’. It seems that the only way out of this evil dead trap is the kind of genuine love, friendship and solidarity which Mitsuo himself, and many of his guests, singularly lack.

Bakemono is a labour of love from the polyhyphenate Doug Roos (The Sky Has Fallen, 2009), who here is not only writer/director, but also editor, cinematographer and producer, as well as composer of the unnerving score and designer of the astonishing practical effects. The creature in the apartment, all inverted skin, externalised bones, clawed fingers, spiny appendages, and eyes and teeth where they should not be, falls somewhere between the Lovecraftian entity from Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession (1981) and the alien predator from John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) – and like both of those, it approximates and assimilates human form, in what is after all a grotesque reflection of all our worst traits, and a monstrous instantiation of Tokyo seen through a glass darkly.

Doug Roos’ time-collapsing apartment horror lets a murderous monster expose the shadowy psyches of a landlord, his tenants and Tokyo itself

ZOEKHETUITMAN

ZOEKHETUITMAN punk music, which is inspired by the goth movement from the late 80's. They are notorious for pulling their audience in an atmosphere that is both ominous and irresistibly alluring. The group’s unparalleled approach to postpunk music is characterized by its cold and groovy drums, cascading melodic guitars and dark wintery vocals.

punk music, which is inspired by the goth movement from the late 80's. They are notorious for pulling their audience in an atmosphere that is both ominous and irresistibly alluring. The group’s unparalleled approach to postpunk music is characterized by its cold and groovy drums, cascading melodic guitars and dark wintery vocals. Strobocops

Strobocops